FORENSIC ARCHITECTURE

Forensic Architecture, a research team based at Goldsmiths, University of London, specializes in urban and architectural analysis of conflict. In the context of research for this report, its methodology was a response to the limitations of site access.

SITE SURVEY

Forensic Architecture’s core team could not access Gaza because of the same restrictions faced by Amnesty International. It therefore worked with a number of field researchers and photographers who documented sites where incidents took place. The photographers followed basic protocols for forensic photography. These included, where possible, step photography, the introduction of scale indicators to each frame, panoramic documentation, GPS location, and the keeping of a handwritten diary of description related to each photograph.

WITNESS TESTIMONIES

On several occasions Forensic Architecture requested additions to testimonies collected by Amnesty International, primarily to clarify spatial information. These additions included asking witnesses to mark their locations on maps, plans or satellite images. Forensic Architecture located elements of the witness testimonies in space and time and plotted the movement of witnesses through a three-dimensional model of urban spaces. It also modelled and animated the testimony of several witnesses, combining spatial information obtained from separate testimonies and other sources in order to reconstruct incidents.

SATELLITE IMAGE ANALYSIS

The Pléiades Earth-observing satellite constellation, operated by the French space agency, CNES, has been collecting images at a resolution up to 0.5 metres a pixel since 2012. While this level of detail is now common for commercial satellite images, American commercial satellite companies such as DigitalGlobe are obligated to degrade any imagery taken over Israel or the Occupied Palestinian Territories to 1 metre due to agreements between Israel and the USA. The Gaza/Israel conflict of 2014 is the first Israeli-Palestinian conflict in which such high resolution satellite imagery was made publicly available (and thus obtained by Amnesty International and Forensic Architecture). “Before” and “after” Pléiades satellite images were used to assess changes in site condition at attack sites under analysis. The “before” satellite image served as a baseline from which any disturbance to the natural or built-up environment may be identified by comparison with the “after” image.

Three satellite images are relevant to this study, dated 30 July, 1 August and 14 August. Each image extends westward from the Gaza-Egypt border to encompass central Rafah and was acquired around 11.39am when the satellite passed over the western Levant. The 1 August image, in particular, captures a rarely seen overview of a moment only two and a half hours after the ceasefire collapsed, at the heart of the operation.

Forensic Architecture’s interpretation of satellite imagery was corroborated by John Pines, a satellite image analyst and former intelligence officer in the British military.

Further analysis of Pléiades and other satellite data was undertaken by Dr. Jamon Van Den Hoek, Postdoctoral Fellow at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center and incoming Assistant Professor and Geospatial Intelligence Leader in the Geography programme at Oregon State University. Dr Van Den Hoek carried out an automated change analysis using panchromatic and NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) data based on Pléiades images as well as open-access NASA Landsat-8 satellite images, which cover all of Gaza. These "change" maps were used to identify building and road damage, locations of craters, and crops or trees destroyed when vehicles were driven through fields. Studied individually and in relation to each other, satellite images provided a useful resource to reconstruct the force movement, blasts and other events of 1-4 August 2014.

MEDIA ANALYSIS

Forensic Architecture scanned a large number of Arabic, Hebrew and English-language sources, many of which were also consulted by Amnesty International. They included Palestinian and Israeli media sources, Palestinian social media sources and photographs and video clips from photographic agencies and image banks. They also included official Israeli and Palestinian statements appearing on IDF and Hamas websites; accounts by Palestinian NGOs, such as the Al Mezan Center for Human Rights, the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights (PCHR) and Al-Haq; testimonies given by Israeli soldiers to Breaking the Silence and published on their website; video recordings from the local ambulance services in Gaza; hospital logs which document calls to the emergency office; photographs and videos provided by civilians and activists who witnessed events. Forensic Architecture extracted further written, filmed and photographic materials from these sources.

VIDEO TO SPACE

While a few independently shot videos were uploaded onto social media during the 2008-9 Gaza/Israel conflict, Forensic Architecture retrieved a comparatively large amount of audiovisual material on social media in relation to the 2014 Gaza/Israel conflict. Photographs and videos taken by both journalists and citizens captured large amounts of spatial information about environments in which events were unfolding, including the architectural layout of sites, the location and the time of day. Video stills were collaged together to create a panoramic view of space. Working back from distinctive architectural features – for example, a water tower, a high building, a crossroads or a football pitch – Forensic Architecture located still images within the satellite images and three-dimensional models.

GEOSYNCING

Geosyncing refers to the establishment of space-time coordinates of an event. To reconstruct the events of 1-4 August, Forensic Architecture employed digital maps and models to locate evidence such as oral description, photography, video and satellite imagery in space and time. As such the media were used to reconstruct events, and to verify findings by cross-referencing various sources. When the metadata in an image or a clip file was intact, Forensic Architecture identified it by using Adobe Lightroom and Adobe Bridge. The geosyncing is in this case a straightforward process, undertaken on software platforms such as QGIS. However, material from social media often came without metadata, or with the metadata damaged or inaccurate. In the absence of digital time markers Forensic Architecture used analogue or “physical clocks” – time indicators in the image – such as shadow and smoke plumes analysis to locate sources in space and time.

METADATA ANALYSIS

Photographs and videos sourced from social media, activists and civilians on the ground often did not have accurate metadata, as cameras are not always set to the right time and date. Forensic Architecture investigated the accuracy of metadata by corroborating the footage with other verified events. Furthermore, Forensic Architecture was able to correct wrongly set metadata, by marking the time difference between the images in a sequence of photographs, and synching the sequence with a recognized and timed event.

SHADOW ANALYSIS

Forensic Architecture built a digital model of Rafah to locate witnesses and photographs in space, as well as to use the model as a digital sundial; all standard architectural modelling software currently come with shadow simulators. To establish the time of a photograph Forensic Architecture matched these digital shadows with shadows captured in a photograph or a video. A match would provide information about the location, orientation and time of the image representation. Another use for shadow is that the length, seen on satellite imagery, provides information about the height of built volumes.

In order to time video footage through the observed shadows, Forensic Architecture undertook a threefold process. First it located the image or still from the video geographically and calculated the camera angle. Using three-dimensional modelling and animation software – such as Cinema 4D – that offers camera calibration features, Forensic Architecture then analysed the perspective and lens distortion of the found footage and matched it to a digital camera perspective. It finally ran a digital shadow simulation, by inputting the location coordinates and seasonal information to find the matching shadows and determine the time of capture of the footage.

In many cases the process was supplemented by an analogue shadow calculation, by architecturally analysing a one-point or two-point perspective, drawing the featuring buildings and shadows into a plan and using an analogue sun diagram to calculate the time of capture. This process is extremely sensitive to measurements and could only be employed with regard to a small portion of the footage, where shadows are clear and orientation can be clearly defined. When used this method was corroborated by other evidence or was used to support alternative time indications. The margin of error is five to 10 minutes.

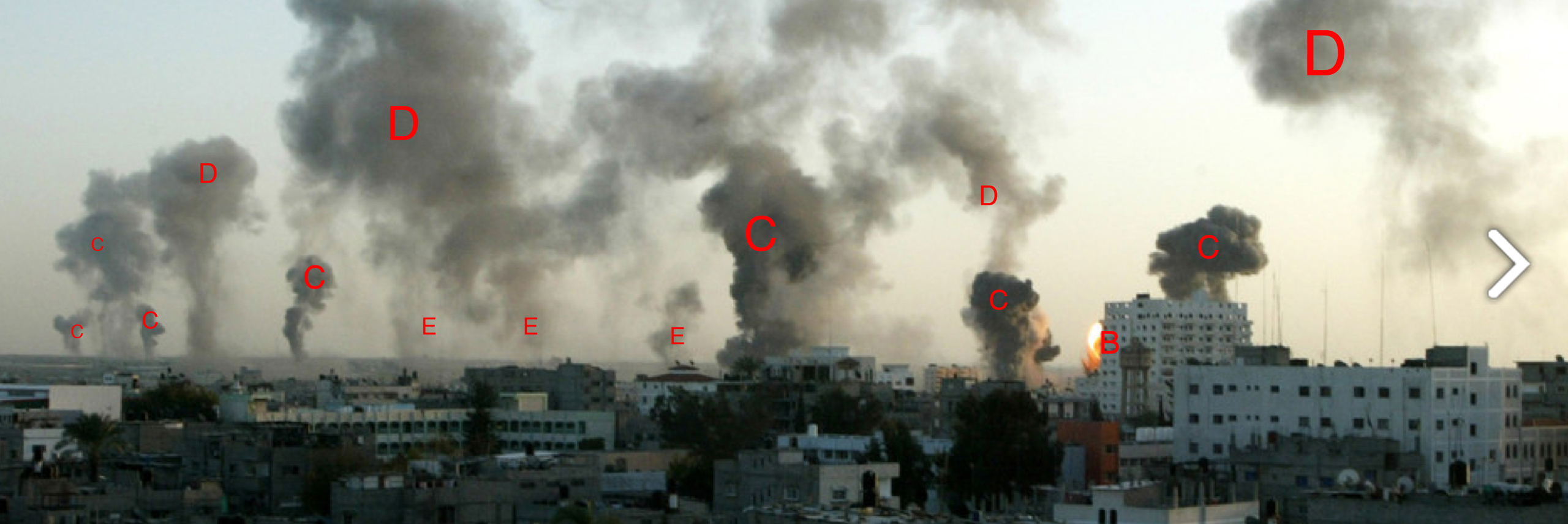

PLUME AND SMOKE CLOUD ARCHITECTURE

After a bomb blasts its smoke plume goes through several distinct phases. The plume forms into a mushroom cloud that slowly dissipates. Studying photographic representation of plumes, Forensic Architecture estimated how long after a strike the photograph was taken. Each explosion from air-dropped munitions results in a smoke plume whose form is unique to the moment and the strike. In this way, Forensic Architecture undertook detailed morphological analysis to identify the same strike in different pieces of footage and to synchronize the footage based on the phase of plume growth being observed. This analysis therefore offered a way of linking evidence together in space and time. The process of synchronization and triangulation helped reconstruct the space and time sequence of unfolding events. Forensic Architecture also measured and compared the size of plumes as captured in different media sources, to compare the plume caused by unknown strikes with known ones.